Far away from here, and many thousands of years in the future, a young girl by the name of Coletta von Nestershaw walks through the empty rooms of the station. Its formal name is very long and tedious, as names of things tend to become when the same organizational scheme has been used to assign them for over a thousand years. It all ends in a number—893. Thus, its three occupants call it Station 893.

Coletta is twelve and has many strict ideas about all sorts of things. One of these is her annoyance over the fact that some things have multiple names. It seems redundant, hampers communication, and makes everything harder to learn. So, while she is not satisfied that the station has multiple names, she accepts it. She is also very fond of her home. She has lived here since she was ten, when her father—Venya von Nestershaw—was assigned to the planetoid in which the station is embedded.

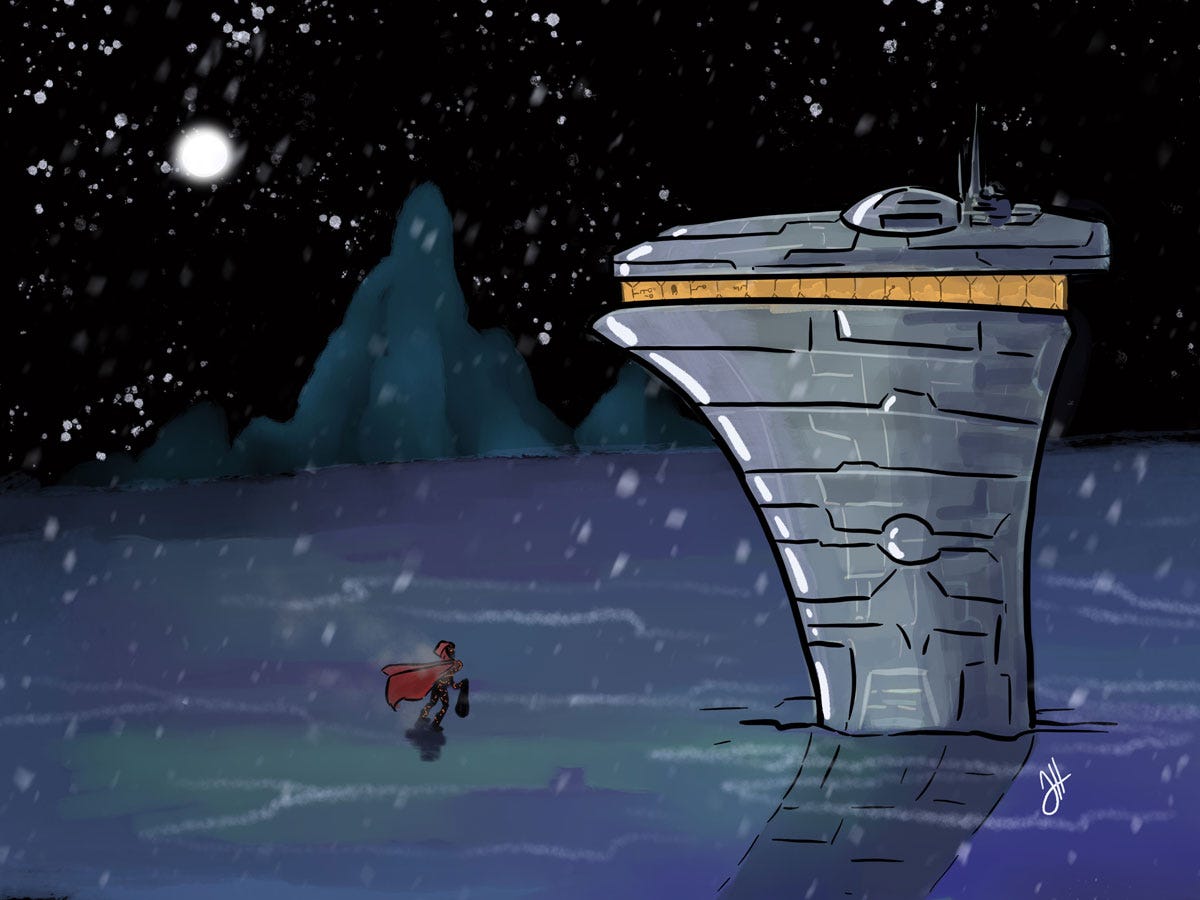

The planetoid has no name, it’s just a seemingly endless series of numbers and letters, so Coletta calls it “the rock” or, more often, “planetoid” because there seems to be no reason to give it another name. It is brutally cold outside, and as far as Coletta can see vast planes of ice recede into the distance. It glitters at sunrise, although the star for this system is very distant. The light will sometimes refract in hues of purple and blue. But now the short day is done, and the sun is hidden.

The station is anchored into the ice—it’s shark-tooth shape sunk deeply in through force and heat. She never tires of the vast emptiness of the rock, but she loves it most of all this time of year. Because she is only days away from Kriznas, and the cold and Kriznas go together.

“It is time to sup, Coletta,” says Nan, the ovoid comfortdrone who has raised her since she was very little, after her mother expired.

“Very well, Nan,” Coletta sighs, stopping the game of leapscotch she was playing in the game room, and bowing her head slightly. A smooth tube slides out of a recessed panel in Nan’s side and attaches itself to the center port in Coletta’s nexum, a cluster of natural ports that all humins have evolved. A puree of fiber and nutrient-rich suspension shoots through the tube, past the center port’s tasting ring, and directly into Coletta’s system. Coletta smiles appreciatively.

“Mmmm. What was that? I liked it very much,” Coletta said. Nan chirped, pleased with herself.

“It is a special mix I’ve been thinking up. It’s called ‘Rain in the Woods,’ If you like it, I can add it to the regular rotation,” Nan said.

“Yes, please. Are you planning a new taste for Kriznas?”

“Perhaps. If you are good.” With that, Nan floated away to attend to other duties. Nan had many bodies throughout the ship, all working simultaneously, so she was never far away. When Coletta’s father was away working, Nan was more than just her comfortdrone. She was the keeper of their residence. Venya operated a large rover and did his scientific work over long sojourns over the ice. The weather on the planetoid was too violent for aircraft. Even the formidable traction of the rover wasn’t enough when the weather was at its worst. So, it was a slow and tedious business, and he was usually gone for months at a time.

“I hope he’s home for Kriznas,” Coletta said, stopping by the nativity on her way to the Kriznas tree. Nan was not physically present, but her warm intelligence permeated the station. Coletta would often speak to her, just to make her thoughts known, without expecting a reply. The nativity was a traditional one, although other families had trendier-looking ones. At least, that was her impression from the shows and commercials she saw on the viewer. They were well out of regular broadcast range, but they got data bursts every six months. It was expensive, because of the raw power needed to send the info, but it kept them at least marginally in contact with civilization. They were due another a few days before Kriznas.

In any case, Coletta had always favored the more traditional set-up for the nativity. Three walls of plantone mimicked ancient wooden walls. Shaved plantone sticks represented the hay. In the center of all this was Mahre*E, the most holy birthing chamber, recreated down to the most minute detail by artisans working in precious metals. Within the birthing chamber was the traditional glowing green egg, made of a spongey, bioluminescent fungus that was meant to mimic the look and feel of the real thing.

“May the light of Josu Kriz, still but a spark in Mahre*E’s womb matrix, guide papa home, safe and sound, on Kriznas morn,” Coletta intoned reverently. Tucked within the green fungus was a genestruct of Josu Kriz, ready to be “birthed” at the appointed hour. He’d emerge from his protective cocoon, deliver the traditional Kriznas speech, and be generally available for play for about a day or two. Then the genestruct would dry up and shrivel, the way all genestructs do, and be pitched in the recycler. But for a couple days she’d have her very own pocket god. It was always very exciting.

“Nan, may I trim the tree?” Coletta asked, as she entered the main hall of the station. Here, the enormous holographic projection of their Kriznas tree slowly turned, hovering above the circular gift pit. The tree itself was also traditional, a crystalline lattice of sharp green spikes emanating from a central, rotating cylinder. The facets of each spike cycled through video memories, stretched and semi-translucent over the length of their surface. The memories were from the collections of all the Van Nestershaws going back hundreds and hundreds of years. The distortion of the shards rendered the memories somewhat abstract, but all were selected for their happiness and nostalgia quotients.

“Yes, my dove,” said Nan as a panel in the wall slid open and one of her ovoid forms glided gracefully next to her. “Would you like me to sing, or would you?”

“Oh, you, please. Your voice is so beautiful.” Coletta raised her hands up to the Kriznas tree, and Nan began to sing.

Guide my hand / Oh Josu

As I shed / The past into

Crystal limbs / Vibrate the call

Reveal the gifts / For one and all

Coletta swiped gently at the jagged crystals near the top (you had to start at the top, it was a rule) and they fell away and shattered into nothingness. You did this a little each day leading up to Kriznas, until finally the base of the tree was swept away, and the gift pit was revealed. This reminded Coletta that she needed to finish and wrap her gift for her father so Nan could place it in the pit. Her father was not a sentimental man. So Coletta had wracked her brain for most of the year trying to think of something practical he’d enjoy on his long sojourns. She settled on a radiation detector, and had Nan add it to their last shipment order—they got shipments only once a year—in secret, using her allowance funds. Coletta had painted it in her favorite colors—purple and blue—and affixed a small picture of herself on one end. It was practical and sentimental, so she hoped her father would like it for one aspect at least.

Oh three-headed god / we wait for you

In your cloak of man / Sweet Josu

The wrath-head God / And Gentle Sonu

Ghost-head Spirri / All are you

Sweet Josu

Sweet Josu

Coletta had tears in her eyes. So great was Josu Kriz. She couldn’t wait to play with him on Kriznas morn.

Weeks passed, and Kriznas grew closer and closer, and the tree was nearly half gone.

“No word from father, yet?” Coletta asked Nan. It was long past her bedtime, but Nan had allowed her to stay up later as a treat.

“No, my dove. Not yet. But the storms have been terrible lately,” she replied. Coletta knew this, of course, because beyond the constant weather map that was projected in the communications room, she also could hear the winter storm battering the walls of the station. Months could go by without hearing from her father, especially when he was on the far side of the planetoid as he was now. The thought that he was on the sunny side of the planetoid made her happy, somehow, as she stared out at the dark, blizzard-obscured night. Although she hoped he was headed back to her. She wanted to give him a hug. It was like hugging a stone, at times, but it gave her comfort when he was near, especially if her loneliness had been severe.

Then, the entrance bell chimed.

This was impossible, of course. But it still sounded.

“Was that the outside entrance?” Coletta asked expectantly.

“I’m sure it’s just some sort of malfunction. Your father isn’t due—well, if he is going to be able to make it back, he’s not due for at least another week,” Nan said. Coletta felt like Nan was acting very odd. The entrance bell chimed again. Coletta ran to the nearest screen and turned on the entrance camera. There was a man, hunched over, with black cracked skin, wearing a ragged blood-red hooded cloak. His eyes burned like cinders. Coletta was delighted and ran for the entrance.

“Now, Coletta, hold on one—sigh,” Nan said, as even her hover engines weren’t fast enough to keep up with the girl. Instead, another of her bodies activated near the entrance.

“Hello, mysterious stranger!” Coletta said into the microphone once she reached the entrance.

“Hello little girl! It is I, Cinder Clod! Come to reward the good little children and mercilessly punish the bad! Which are you, little girl?” said the man, who was clearly her father in disguise. Nan and he had conspired to surprise her, although apparently, he was earlier than expected.

“You’re supposed to know!” Coletta crossed her arms and acted unimpressed. “Where is your great data cloud, that collects all children’s thoughts and deeds?”

“Oh, good point,” said Cinder Clod as he touched one finger to the cracked black skin of his temple. Smoke hissed out from between the cracks. “Ah, yes, here’s the data. I have the decision on you. Now let me in before my cinders completely cool!” Coletta giggled, and let “Cinder Clod” in.

“You must be the comfortdrone, eh?” Cinder Clod asked Nan.

“Yes, oh great Cinder Clod, I am,” Nan said, a little stiffly. “Coletta, dove, run to the refinery and get a nutrient suspension for Mr. Clod, here. We don’t want to break with tradition.” Coletta nodded and ran away excitedly. She’d helped Nan brew the suspension. It tasted like Ginger Surprises, and she knew her father would love it. As she ran away, she heard Nan whisper to her father. Even though Nan’s voice was low, she still heard her.

“You’re awfully early, Sir,” Nan said.

“Am I?” Cinder Clod asked. “Huh.”

The conversation was over by the time Coletta returned with the vial of Ginger Surprises, wrapped in festive mauve paper. She handed it to Cinder Clod with a quick curtsy.

“This looks wonderful,” Cinder Clod said, raising the vial up to his mouth.

“No, Cinder Clod!” Coletta squealed in delight at her father’s silliness. “Not in your mouth!” The man seemed genuinely chagrined, and her father’s acting made Coletta even happier than she had been. Sometimes her father could feel as distant as this system’s sun, even when he was at home. He got wrapped up in his work, and his job wasn’t easy. So, it made Coletta happy when he went through some extra effort for her. It was rare, and always welcome.

“Well, where, uh, do I put it?” asked Cinder Clod.

“In your nexum, of course,” Coletta said. Cinder Clod stared at her blankly. Her father was really leaning into this performance.

“Perhaps I can do it for you, Sir—I mean, Mr. Clod,” Nan said. She took the vial from Cinder Clod, and hovered behind Coletta’s father, who continued to keep up the charade of confusion. Nan froze and hovered in place.

“What’s wrong, Nan?” Coletta asked. Nan didn’t respond, but Coletta heard the gentle whir of a panel opening behind her. Another of Nan’s bodies was at her side. Then another one came, speeding down the corridor from the main hall.

“Is something wrong?” Cinder Clod asked, his orange-flame eyes darting behind him, as a swarm of Nans surrounded Coletta.

“This isn’t your father, dove,” Nan finally said.

“Of course not! I’m Cinder Clod, one of the servants of—”

“Cut the act. And tell me who you are.”

“I don’t understand! Of course, that’s father!” Coletta said, her head darting from one Nan to another as they surrounded her.

“This person has no nexum, dove,” Nan said. Hovering near “Cinder Clod” threateningly.

“Oh. Yes, yes, I see it now,” said Cinder Clod. And Nan watched as three holes appeared in the base of the man’s neck. “I’m sorry.”

“You’re not my father?” asked Colette. The man kneeled, and the Cinder Clod disguise melted away from his skin and seemed to evaporate, leaving behind her father. Or what looked like her father.

“I’m not, Coletta. But I could be,” said the man.

“Enough. You will reveal your identity, and then you will be detained until the proper authorities can be contacted,” Nan said. “You will not get anywhere near the girl.”

“You’ve… you’ve got this all wrong,” said the man. With these words, the likeness of Venya von Nestershaw melted away, too. In his place, appeared a man who looked like he was made of ice. Except, when Coletta looked closer, she could see that under the frosted crystalline exterior were vague suggestions of organs. They showed as blooms of color—reds, blues, and purples—peeking through the foggy glass of the creature’s body.

“What are you?” Coletta asked softly, before asking the question she most wanted to ask, but most feared. “Where is my father?”

“I have no name but the one you gave me,” the creature said, kneeling so that it was eye to eye with Coletta. The Nan bots hovered nervously around the girl. “It is apparently very long. So, you call me Planetoid. Which is as fine a name as any.”

“You—you’re the planetoid?”

“Sort of. I suppose I’m not that different than your protector, here. One mind, many forms. When you first came here, a literal thorn in my side, I was very annoyed. But over time I have come to care for you, Coletta. And your father. He liked to poke me, and bore holes in me, but I suppose I liked the attention.”

“We will assume that’s true,” Nan said, hovering lower so that she was between Planetoid and Coletta. “But the girl asked you another question. Where is her father?” At this, Planetoid’s rudimentary crystalline face frowned.

“I am sorry. And sorrier to be the one to deliver the news. His rover broke down, and he could not contact you. He tried to get back, but he was so far away. I showed myself—I wanted to help him, protect him, on his journey home. But I scared him. He ran and fell off a sheer ice cliff. I could not save him.”

Nan let out a small, electronic squeak. Coletta, for her part, stood very still.

“Where is he now?” Colleta asked. The Planetoid looked toward the main entrance.

“I froze him in ice. You have many wondrous machines. I didn’t know if you might have something—I mean if he was kept very cold if there was a chance—”

“We have a DocBox, but it would depend on the extent of…the injuries,” Nan said carefully, the main, hexagonal light in her body pulsating yellow, which it always did when Nan was deep in thought. “But there is a chance—if we could use the DocBox while keeping him in stasis until he can get proper medical treatment. It will take many months before a ship can come retrieve us. I will contact the corporation.”

“I can regulate his temperature. Below my surface,” said the Planetoid. He closed his eyes for a moment. “There. I have pulled his form into myself. I can keep him at whatever temperature you need.”

“I will grab the DocBox. Can you pull me below too? I would like to stay near him and monitor him,” Nan said. The Planetoid nodded. Nan was gone for only moments before she returned with the suitcase-sized DocBox. Nan did not say goodbye to Coletta, of course, because she was still all around her, and had many more bodies, but she did turn back briefly and look at the young girl. Colleta was so still, and so silent. Nan cycled through a thousand different possible grief counseling options, before deciding that she should give Coletta a little time alone to process. She floated out to the planetoid, blasts of cold air and snow gusting in. And then door shut.

“She’ll be safe, don’t worry,” Planetoid said. Coletta nodded, and then turned away. She walked, a little mechanically, to the main hall. She sat on the long gray couch near the Kriznas tree. The Planetoid, not knowing what to do with himself now, sat on the couch too, some distance away from her.

“Is there anything I can do?” it asked.

“Why did you pretend to be him?”

“Your kind seem to hold some day-cycles in more regard than others. I rushed down to your father as he—well, I was there with him for a few moments. I’m very good at reading thoughts. They sort of blast out toward me, to be honest. And his final thought was of Kriznas, and you, and how he planned to surprise you.”

“It was?”

“Yes. You seem surprised.”

“Maybe a little,” Coletta said, because she did not want to say what she really felt. She loved her father, in a way. And she knew he loved her, in his own way. But they were more like two people who lived in the same space than family. Coletta would have named Nan as her closest kin, if someone had ever been around to ask. He was gone most of the time, so his presence provided something comforting but non-specific. Not the comfort of a father, who has returned to his child. But the comfort of another living being, with distinct ideas of their own, occupying the same space she was in. The thought that he was gone, now—perhaps permanently, sparked strange and conflicting feelings within her. There wasn’t a lack of grief, but she wasn’t sure if it was because of the loss of her father, or because of the loss of an occasional companion.

“He did love you,” Planetoid said. Coletta whipped her head around in confusion, before realizing that it had said it could read her thoughts. “I’m sorry. I’m not trying to read your mind. You’re practically shouting at me.”

“I think he loved you,” Coletta said.

“Yes, he did,” the Planetoid said, turning its head toward the Kriznas tree. Tilting it slightly, as if trying to take in everything it saw there. “Or, to be precise, he loved the puzzle I represented. He loved that about you, too. Because you were no less baffling to him. But he also loved you like you love me—for who and what you are. You love my icy expanse. My wild and untamable nature. He loved your specific, fervent beliefs, as well as the puzzle you presented. He loved your efficiency, even as he worried that being raised by a robot might have had a negative effect on you.”

“You learned all of this as he—as he expired?” Coletta asked. Planetoid shook its head.

“No, as he drilled out core samples from me, I explored his inner recesses as well. It only seemed fair.”

“I suppose. And me? Did you explore my mind as well?”

“As you stood at the window, staring at me, your love radiated. I did not have to dig in for it. I just sat back and enjoyed it,” said the Planetoid, a smile forming on its face. “In all my long days, I have been respected, feared, enjoyed, and hated. But never loved. In any case, I pretended to be your father because I wanted you to share the upcoming day with him without sadness.”

“That was thoughtful. But we humins don’t like being tricked,” Coletta said, inching closer to the Planetoid. Coletta realized that most of her knowledge of humanity came from shows, and that perhaps that wasn’t a true judge of her race’s wants. So, she adjusted and limited herself to her own feelings. “I’d rather have reality. Something reliable. Consistent.”

“Hmm,” said Planetoid. He sensed what Coletta wanted, and he inched forward toward her, and put his arm around her, and pulled her close to him, protectively. Coletta rested her head against his chest.

“You’re warm. I thought you might be cold.”

“I would have been when I first came in. But I’m not made of ice. It’s more like crystal. And it absorbs heat quickly,” said the Planetoid.

“It’s nice. Like a massage stone,” said Coletta. “Now why did you say ‘Hmm?’”

“Well, you are a very young girl,” the Planetoid said, watching the Kriznas tree rotate. “I am very, very old. And I have had many different beings wander my surface over that time.”

“And you’re very wise, then, I suppose?” asked Coletta. The Planetoid laughed, and its laughter had a musical, vibrational quality to it.

“Less that, I think, than I’ve had a lot of time to think and come to some conclusions.”

“Like what?” Coletta asked, yawning, letting her head further relax on the warm, unyielding surface of the Planetoid.

“Well, the universe is a very wild place, full of things that are out of our hands. I cannot control who lands on my surface, for instance. I do not control my orbit around the star I have called home for millennia. But we like the illusion of consistency—to believe in the unbroken chain of what we call reality.”

“I don’t understand,” Coletta said sleepily.

“I know, sweetheart,” said the Planetoid. “But most beings in the universe are little more than a flicker. Blink and you’ll miss them. So, they like the idea of permanent things—places or ideas, mostly—that are a bedrock against the unruly change that is around them. But when you’ve lived as long as I have, you know that most of those things are flickers too. Two thousand years or two months or two seconds—the difference becomes barely noticeable after a while.

The best you can hope for is something malleable enough to twist and fold with the wildness of the universe. But sometimes, that new shape is so unrecognizable as to barely resemble the thing it once was. I think there’s beauty in that, though, too. Because that new thing might be greater than the thing it used to be.” Coletta snored softly by the Planetoid’s side. It scooped her up its arms and carried her to her bed. It laid her down gently there and pulled her covers up around her head. As it exited, it saw Nan float toward it.

“You tried to call, I take it,” the Planetoid said.

“You knew there’d be no answer,” Nan said.

“I did.”

“Mr. Van Nestershaw’s body is shattered. There is no hope of recovery for him.”

“There is not.”

“Why? What does this mean? Why did you give the poor girl hope where there is none?”

“My kind exist all throughout the galaxy. We can speak to each other, through the song of cosmic tides that your kind cannot see or hear. They brought me news of your makers’ misfortune some months ago,” said the Planetoid.

“What happened?”

“A solar implosion destroyed your home system. There is not much left of the civilization you left behind.”

“Those words you said, when Coletta was asleep. They were for me more than her.”

“Yes, she understands a lot for one so young. But would not understand this, I suspect,” the Planetoid said, as its features blurred and remolded back into the form of Venya Von Nestershaw. “Because there is no future for her beyond me—beyond this small station and this icy rock. I wish to make the future she does have as comfortable as it can be. With your help I can do that. But you know her best.

Which should that future be? As her father—after a “miraculous recovery” thanks to your DocBox—or as myself? I do not know the best course of action. I know what she says, but it is at odds with her heart. Which should I listen to?” Nan floated over to the doorway leading to Coletta’s room.

“We are probably both poor judges of that,” Nan said. “I cannot say if my thoughts and feelings are my own, or just clever programming. And you—your mind and your perspective I can only guess at.”

“It’s not ideal, true. But we’re all she has,” the Planetoid said. Nan let out a chirp of agreement, and she and the Planetoid watched Coletta as her body, buried under the thick blue comforter she was tucked into, rose and fell gently. They regarded this little creature, suspended between youth and adulthood, apocalypse and comfort, loss and hope, and could not find the answer to their quandary.

“We will decide in the morning,” Nan said.

“Yes, that is wise,” said Planetoid. And then both watched Coletta sleep, as the unrelenting storm around them howled and clawed at the station.

The End

Notes on “Kriznas on Station 893”

In mid-September of this year, I began thinking about what I’d do for my December short story. I had some options I’d already written, but I liked the idea of doing something new. I started with the idea of a little girl celebrating Christmas, or at least what was left of the IDEA of Christmas after thousands of years. There’s a whole backstory to how humanity got to this place. Maybe someday i’ll tell it. But for now, it’s just about Coletta. I was not expecting the story to take the turn it did.

Maybe it’s an extension of my own thinking about the holidays. I love them, but there’s no denying that the holiday is tinged with sadness for many. I’m always very much aware of this, and I think that seeped in here too. The story got “bigger” in ideas than I expected, too. I like the strange brew of what it ended up as. I hope you do as well.

About the music:

What Is Love by Kevin MacLeod

Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/5015-what-is-love

License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Share this post